A Tribute to our Australian and New Zealand ‘British Nuclear Test’ Veterans on ANZAC Day

On 25 April each year, Australia and New Zealand commemorate all Australians and New Zealanders “who served and died in all wars, and peacekeeping operations”. “The contribution and suffering of all those who have served” is also commemorated on this day, known as ANZAC Day.

ANZAC Day was originally devised to honour members of both Commonwealth Armed Forces who served at the Gallipoli Campaign during the First World War. As part of their service in “peacekeeping operations”, the British Nuclear Test Veterans’ Association remembers those who participated in the British nuclear tests at Operations Hurricane and Mosaic at the Montebello Islands, Operations Buffalo, Antler and Totem in Australia, and Operation Grapple during the 1950s and 60s.

The British atomic weapons programme commenced in 1947, and the British, reacting to competition from the USA, were ready to test the effects of a nuclear weapon. This initial test, Operation Hurricane, took four years of planning, and was designed to mimic an attack on a British harbour by detonating a 25-kiloton plutonium device in the hull of the frigate HMS Plym.

The HMAS Hawkesbury joined the British before Operation Hurricane at Fremantle, Western Australia, and ten Royal Australian Navy (RAN) warships carried out security patrols around the Montebello Islands. Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Lincoln bombers took off from Broome, Western Australia, to reinforce security patrols above and around the Montebello Islands and the Indian Ocean, as part of Task Force 4, alongside the British Armed Forces.

The detonation in the hull of the HMS Plym caused a crater of 6 metres deep and 300 metres wide on the ocean floor, with a mushroom cloud rising to 4.5 km into the atmosphere. The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), based at Whenuapai, assisted with the monitoring of radioactive fallout during Operation Hurricane; they conducted flights to the North and South of Auckland and a return flight to Suva. RNZAF personnel in Fiji collected rain-water samples for radioactive measurement, along with the Royal Air Force (RAF), who carried out a similar task at RNZAF Base Ohakea 2. The RAN continued regular patrols around the Montebello Islands until 1956.

In 1956, Australia and New Zealand continued to support the development of atomic and thermonuclear weapons by their allies, the USA and Great Britain. Both Armed Forces became involved in Operation Mosaic from the outset, at the Montebello Islands, Operation Buffalo at Maralinga, Australia, and Operation Grapple on Christmas Island. At the Montebello Islands, the HMAS Warrego and HMAS Karangi investigated moorings, surveying and marking operations before Operation Mosaic, and assisted the Royal Engineers and Royal Navy in site preparation work. This included the building of a shore camp, camera tower and weapons towers on Trimouille and Alpha Islands. Commodore Hugh Martell of the HMS Narvik took control of this designated Task Force 308, which included the HMAS Junee, Fremantle, MRL 252 and MWL 251. The RAAF performed cloud sampling through radioactive fallout with the RAF.

Eleven New Zealanders, taken from all three services, became part of the Indoctrinee Force (a British initiative). They were sent to gauge the effects of nuclear explosions orchestrated by Sir William Penney, leading British nuclear scientist who had previously worked with Robert Oppenheimer on The Manhattan Project in the US; Penney had led on choosing the geographical locations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in 1945. He chose both locations to cause maximum destructive impact on human life, as the areas were surrounded by hills. The New Zealanders were sent to these tests to pass information onto their colleagues regarding the impact of ionizing radiation.

The New Zealand Indoctrinee Force were ‘volunteered’ to visit the area around Ground Zero during nuclear testing at the Operation Buffalo tests in September and October 1956, and Operation Antler in 1957. On 27 September 1956 during Buffalo One Tree, the New Zealanders were told which apparel to wear, were told to stand at 8.2km from Ground Zero and turn to watch the blast two seconds after the bomb detonation. They tested the protective values of different types of clothing for military activities, weapons and equipment to pass on the information to colleagues. The officers who took part were put at a high risk of receiving a maximum dose of ionizing radiation directly after the explosion. Doses received are still a debatable subject, as the British scientists and government denied a harmful exposure to the men involved. As a response to public concern, the eleven men were followed up for health effects due to these activities in observing the effects of the nuclear tests – six were alive aged 71-87, five were ages 54, 59, 67, 71 and 81 at time of death. The New Zealand Ministry of Health concluded that the deaths weren’t linked to any observation at the nuclear tests despite retrieving a memo stating that these men would “be subject to radiation hazard”.

The Australian Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, was only too happy to oblige the British requests and volunteered Australian personnel to participate in the British nuclear tests on the Aboriginal sacred lands of South Australia. This followed the Maralinga Agreement in 1954, where Howard Beale wrote in a top-secret Cabinet document,

“Although (the) UK had intimated that she was prepared to meet the whole costs, Australia proposed that the principles of apportioning the expenses of the trial should be agreed whereby the cost of Australian personnel engaged on the preparation of the site, and of materials and equipment which could be recovered after the tests should fall to Australia’s account”.

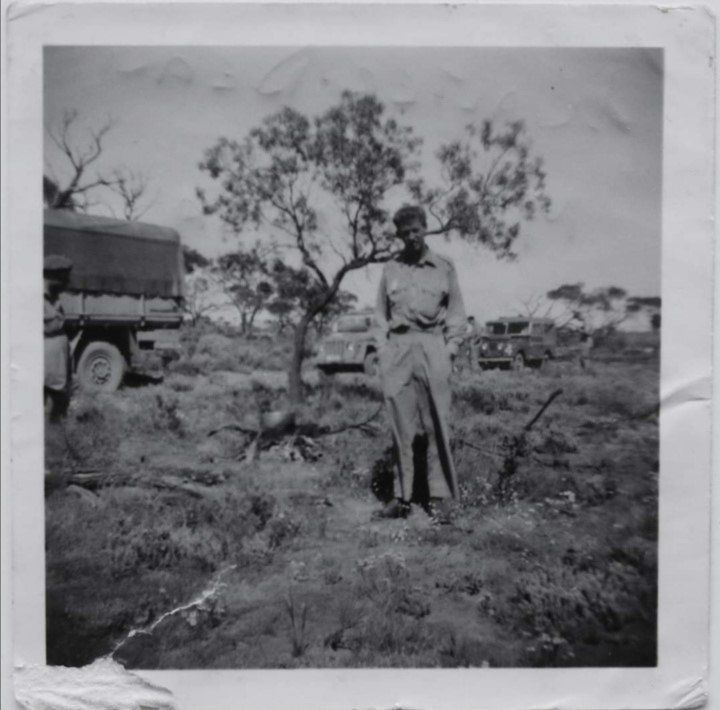

On 27 September 1956 at Operation Buffalo One Tree, Maralinga, the atomic cloud which followed an air drop bomb rose 10,000 feet higher than predicted. This caused a plume of hazardous radioactive fallout to travel over the populated areas of East coast of Australia, including Queensland. Two Australian battalions and reconnaissance troops were ordered to carry out a full-scale brigade advance to ground zero shortly after impact, to test experimental radiation detection and monitoring equipment under design and development for use by soldiers, sailors, and aviators. The RAAF joined with the RAF cloud flyers to fly through radioactive fallout and take readings of radioactivity after the Operation Buffalo tests. These 'hot' aircraft were cleaned up by RAAF personnel; many died at a young age from cancers.

During 1957-58, the UK conducted Operation Grapple off Christmas Island and Malden Island in the Pacific, using air bursts. New Zealand Naval Loch-class frigates, the HMNZS Pukaki and HMNZS Rotoiti, left Auckland at 0900 hrs on 14 March 1957, equipped with radiation monitoring equipment. Both frigates were used as weather ships and were stationed for four tests off Malden Island during May and June 1957 (Pukaki and Rotoiti), one test at Christmas Island on 8 November 1957 (Pukaki and Rotoiti), and five tests off Christmas Island during August and September 1958 (Pukaki). Between the tests, the New Zealand crews spent time on Christmas Island with the British servicemen.

On 29 April 1958, HMNZS Pukaki sailed through surface zero the day after the Grapple Y test, a British bomb with the biggest yield ever tested. Crewmen were fitted with radiation badges, but the badges weren’t processed, supposedly due to problems with storing the chemicals needed to achieve this. A failure to process dosimeters (radiation film badges) was commonplace at the tests by all Armed Forces, with just verbal comments concerning the ‘minimal’ radiation dangers encountered by the men. Three New Zealanders witnessed Grapple tests from HMS Alert.

Additionally, from 1953-1963, a series of Minor Trials testing beryllium, plutonium and uranium took place on the Woomera Rocket Range in South Australia. Australian Army and RAAF personnel assisted at these tests, from the groundwork to cloud sampling.

As veterans and family members of the British nuclear tests, we are all victims of the irreversible events that we believe have affected our genetics, changed our thought processes, impacted inherent values, challenged our personal and social ethics, affected our trust of others, destroyed personal relationships and have made us question our governments. We remember the Australian and New Zealand servicemen who participated in these nuclear tests, many of whom suffered with cancers and passed away many years ago, or struggled with failing health for decades. We also remember their families. We thank the service personnel for their participation and remember their sacrifice this ANZAC Day and every day.