An unexpected experience at Christmas Island.

An unexpected experience at Christmas Island.

The following article, featured in the Autumn 2020 edition of Transmitting, the Museum of Communication Foundation Members’ Newsletter, is written by John Lax, BNTVA Secretary. John volunteered to go to Christmas Island in 1961, without the knowledge that he would soon be participating in the US tests of Operation Dominic. John’s father was in the Army and served at Operation Grapple, making John both a veteran and descendant of the nuclear tests.

On a Wednesday in September 1961, I left a comfortable billet at RAF Hullavington to start my journey to a remote island in the Pacific Ocean called Christmas Island. This journey included stops in New York, San Francisco and Honolulu, then on to my destination.

This was quite an adventure for a 20-year-old who had trained as an RAF Air Wireless Mechanic just one year ago. This final leg of the journey was to be in an RAF Hastings C2 aircraft, a four engine, propeller driven transport aircraft with no sound insulation which made the six-hour flight less than comfortable.

Christmas Island is a coral atoll, the highest point on the Island being just 5 feet above sea level and was to be my home for the next twelve months.

Once settled in, I started work in the Radio Bay at the airfield, the Radio Section consisted of just four people, a Corporal and a SAC Air Wireless, and a Corporal and a SAC Air Radar. The building was a thatched hut in a coconut plantation near the airfield. When we suffered any strong winds, the nuts would fall off the trees and damage the roof so we would not only repair/maintain radio equipment but also became reasonable efficient thatchers.

Hastings aircraft carried an HF communication set called STR 18 and VHF communication sets; in addition, there was a Radio Compass and a Radio Altimeter (never used), useless over sea.

When an aircraft was going to Hawaii, we would carry out a “Route Before Flight Check”. This consisted of a functional check of all equipment, so we would call the Tower on HF and VHF, the functional check for the Radio Compass would be to tune it to a radio station on Oahu called KORL Radio. This signal was in line with the centre line of the runway at Hickam Field. It was easy for us to tune in to KORL, because at 0600 the ionosphere was sufficiently low for us to get a strong signal, and then the Navigator could follow the signal and listen to music all the way to Hawaii. Landing at Honolulu was rather strange, because the International Airport shared the runway with USAF Base Hickam, so, as you landed, the left side was military aircraft of all sizes and the right side was the civilian airport.

An additional equipment on the Hastings was a small intercom amplifier; a simple device which very rarely gave any trouble. I was rather surprised when the Flight Engineer informed me that the intercom was intermittent. What also surprised me was that this gentleman had quite a severe stutter, and I wondered how he managed to become aircrew with such an impediment.

Despite investigation, I was unable to reproduce the alleged fault, then I was informed that the offending aircraft was to be air tested for investigation of an engine fault, so I invited myself on the flight. During the flight, the Radio Operator asked me what I was doing, so I explained. He laughed and told me to ignore it as the Engineer who reported it had built-in intermittency!

As well as the large transport aircraft, we also had Captain Flit, an Auster aircraft converted for spraying DDT over the Island to keep bugs at bay, hence the name. The Pilot of this toy was the Station Adjutant who only had two ambitions: to spray DDT over the Army personnel as they walked from the Mess Servery to the Dining Hall and to remove the antenna that was erected by a Radio Ham. This aircraft had a VHF Radio on board, but with just 3 crystals in it; the obligatory International Distress frequency, 121.5 Kilo cycles, and the two Tower frequencies, and was never a problem as far as air Wireless was concerned.

Communication was, generally, not a problem, the usual meteorological interferences sometimes caused a headache, but we coped. Then in 1962 the Americans arrived, en masse, their first two aircraft arrivals produced more personnel than we had in the three British Services combined.

This was the start of Operation Dominic, which we later discovered was to be a series of Nuclear Bomb Tests. The Americans were so well organised, they forgot to send any Groundcrew for the first week, so we had to form two shifts to handle up to 10 aircraft each day, including weekends. In addition, we had to keep our own aircraft flying.

The build-up to the tests progressed; we were issued with our Safety Equipment, a pair of very black goggles and a Radiation Dosage Film Badge. Our instructions were: at 10 minutes to detonation we should assemble on the football pitch wearing long trousers and a long sleeve shirt and sit with our backs to the blast. All the tests were scheduled for 0500 so we would be roused from our slumbers by a very loud tannoy broadcast: “This is Mahatma, the time is T minus X minutes and counting” The response this message got cannot be repeated, but suffice it to say it was less than polite.

As it was always dark when the tests took place, the fireball would change the sky to blue so in typical military humour, this event became known as a “bucket of sunshine”.

A side effect of these events was the slight interruption in the signals traffic. This was nominal as all the detonations were airbursts, but at low level, and about 30 miles away. The full programme of 25 tests, we are led to believe, caused little damage to the area but I believe fishing was not recommended in the area around the drop zone.

One test did, however, cause some disruption; this was a device known as a “Rainbow Bomb”, it was detonated on the edge of space and, apparently, ruptured the Van Allen Belt and disturbed the Ionosphere thus making long range communication impossible and grounded all flights from Hawaii to Australia for a few days.

When the tests were completed and the Americans all went home, we settled back into our more relaxed ways, we played football and cricket drank NAAFI beer and generally got on with our jobs.

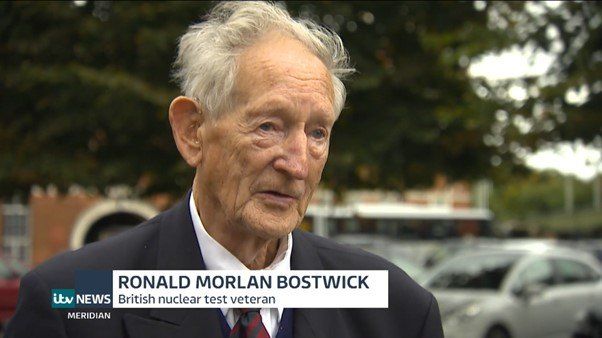

There is a downside to all of this because our protective equipment was less than adequate, many British Servicemen have suffered debilitating ailments and are still suffering. The British Nuclear Test Veterans Association believes there are still 1500 Veterans who were involved in various tests not just Christmas Island and are campaigning on their behalf.

John L W Lax

Trustee BNTVA.